As the nation approaches the dog days of summer, some good news has appeared in the criminal justice space. According to Jeff Asher of AH Datalytics, the national murder rate is on pace for a potentially record decline–currently about 12 percent–over the course of one year. While Asher urges caution in predicting what can happen between now and December, current data suggest a massive drop in homicide victimization and an modest drop in violent crime. Overall crime trends are more ambiguous, but there is reason to be optimistic.

First, the bad news

Although murders are down nationally, homicides are up in almost one third of the cities Asher surveyed, including here in Washington, D.C., where the death toll is 17 percent higher than this time last year.

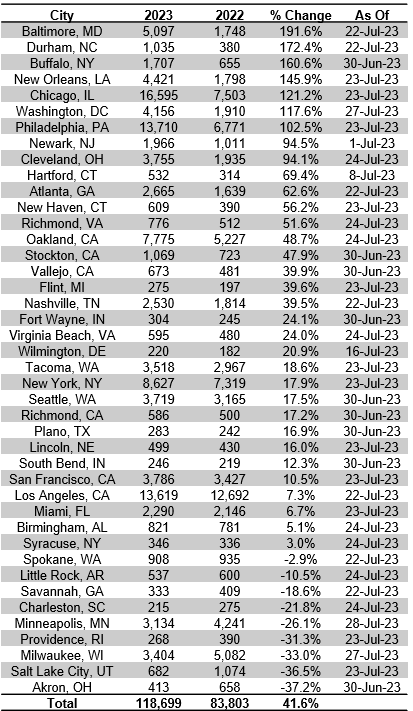

Moreover, there has been a shocking spike in car theft in the past year across the country, leading to a significant increase in property crimes. The car theft spike has been so large that, quoting Asher, “Removing auto thefts from the property crime counts in the 42 city sample would change the [year-to-date] difference in property crimes from +6 percent to -2.6 percent.” While this makes the remaining property crime numbers look pretty good, the car theft stats are obscene. Here in the District, car theft has more than doubled–117.6 percent–with more than 4,500 automobiles stolen so far in 2023. And D.C. isn't even the worst.

Murders and other violence usually earn the headlines–if it bleeds, it leads, the media adage goes–but the explosion of car thefts is unacceptable. Whether the spike is being driven by joyriding kids inspired by TikTok or something more sinister like organized crime, the downstream effects will cost communities dearly.

Individually, someone who loses a car to theft will have their lives disrupted to some degree, depending on their level of car insurance, to say nothing of the personal violation of losing something so valuable. The worse-off someone is economically, the more difficult it will be for them to recover from the loss, particularly if their insurance does not pay for a suitable replacement.

Collectively, car insurance rates will rise and Americans who live in places where car thefts are rampant will literally pay the price for the higher risk of theft and damage. And again, those who are scraping by will have the hardest time meeting the higher premiums, even if their car is not stolen.

Some non-criminal justice fixes are available for some at-risk car owners. Just last week, D.C. provided free software upgrades to Hyundai and Kia owners–the cars targeted in the viral TikTok videos–to make theft more difficult. But thefts are not just limited to those brands, as recent New York State data show that only one model of Hyundai and no Kias made the list of top 10 autos most likely to be stolen in the state in 2022. Of course, owners should park in well-lit spaces, remove valuables from their car, and use other anti-theft deterrents to make their car even marginally harder to be stolen. A determined thief may be able to overcome whatever a car owner tries, but in cities where cars and opportunities to make a quick score are nearly ubiquitous, sometimes a little more effort goes a long way.

But at the end of the day, police will need to help decrease car thefts, whatever the underlying reasons for this increase. Such actions may include increasing dedicated traffic enforcement in areas where cars are going missing. Underaged joyriders are not typically the most responsible drivers and thus upping reckless driving enforcement could yield results, and certainly it would make the streets safer for everyone else in any case. (N.B.: Such enforcement should focus on underaged, bad, and irresponsible driving, not simply driving in the neighborhood. I have written extensively and testified against the policy of pulling drivers over for no reason and looking for crimes police have no reason to suspect.)

The good news and what to do next

While it is far too soon to celebrate a massive drop in homicides for the year, the trend is a very encouraging rebuke of tough-on-crime commentators who insisted the protests of the last few years had made America unsafe again. As Asher notes in the Atlantic:

Murder is down 13 percent in New York City, and shootings are down 25 percent, relative to last year as of late May. Murder is down more than 20 percent in Los Angeles, Houston, and Philadelphia. And, most significantly, murder is down 30 percent—30 percent!—or more in Jackson, Mississippi; Atlanta, Georgia; Little Rock, Arkansas; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and others.

Other cities experiencing reductions of more than 20 percent include Baltimore (22 percent), Charlotte (27 percent), and San Antonio (40 percent).

Although both political parties like to point fingers at the other, these represent both red states and blue ones; big cities and smaller ones. While no one can be sure as to why these numbers are going down, that more than two thirds of the cities reporting homicide data are holding steady or trending lower than last year is a very welcomed improvement.

That said, the problems of antipathy and mistrust between poor minority communities and the police persist. Police departments must fulfill their responsibilities to hold bad officers accountable and make communities safer without treating its members like criminals. These are basic requirements of government officials in a free society, and the protestors who flooded streets across the country knew too often American police officers and departments were failing to live up to them. The crime fear mongering of the last election cycle should not derail efforts to improve police accountability.

Although a mixed bag of good and bad news, preliminary 2023 crime data should reassure policymakers that they can make communities safer and build public trust in police at the same time.