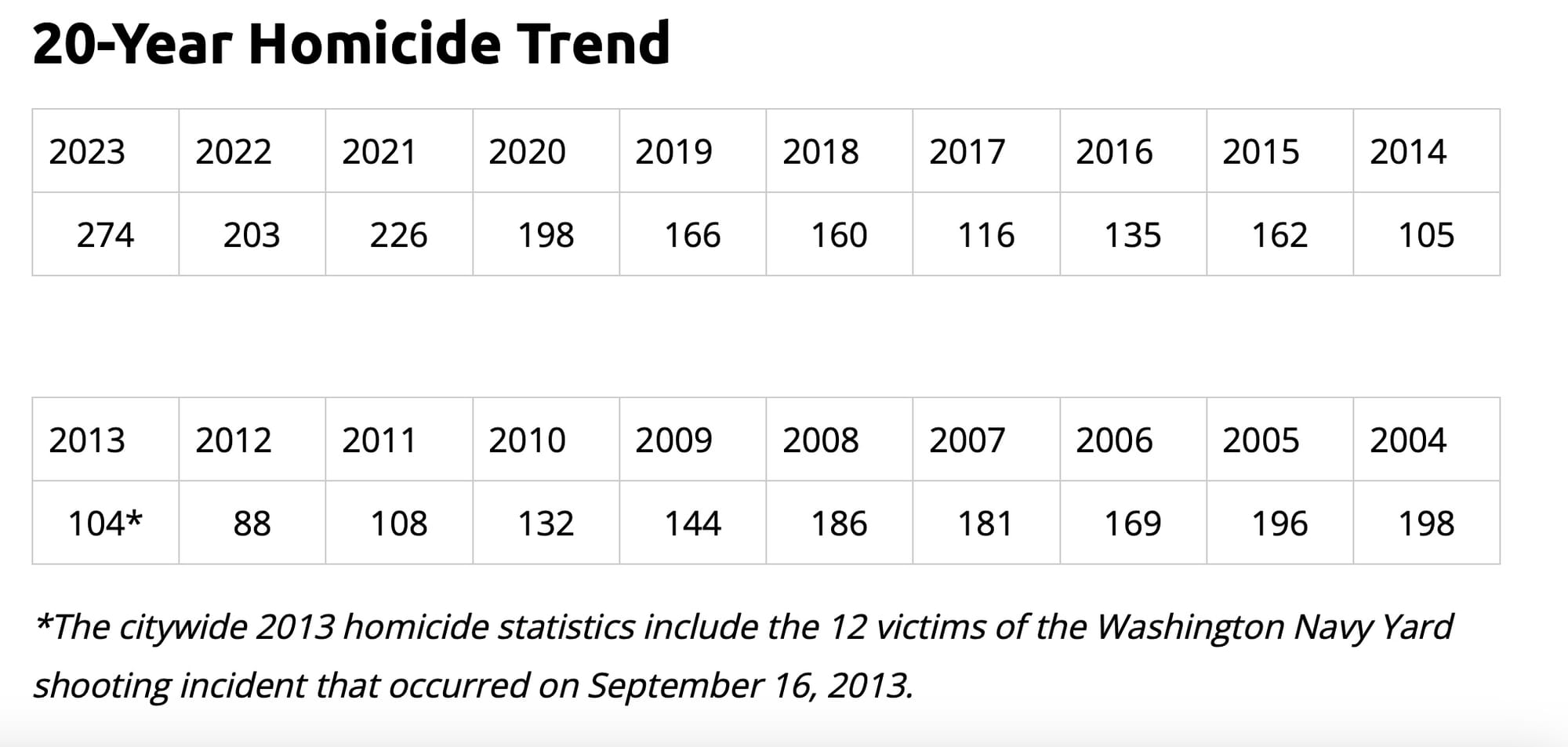

Last year, I wrote several times that Washington, D.C. was bucking national crime trends–and not in good ways. While serious crimes trended downward across the country, D.C. crime increased significantly in most major categories in 2023, with shocking numbers of homicides and auto thefts. All told, relative to 2022, reported violent crime was up 39 percent, reported property crime was up 29 percent, reported motor vehicle theft increased a whopping 82 percent, and the District’s homicide total–274–was the highest it’s been in the last quarter century. Each of the last three years, D.C.’s homicide total eclipsed 200 victims, the three highest totals since 2003.

Politics versus reality in crime policy

The political response has been predictable: undo the reforms passed in the wake of the nationwide police protests. The timing of the protests roughly corresponds with the local violent crime increases. However, as any respectable policy wonk will warn: correlation does not mean causation.

The D.C. City Council passed emergency legislation in 2020 that focused on increased transparency and accountability for police officers. The legislation included a reallocation of $15 million in police funding to alternative strategies like violence interrupters and related social programs to prevent crime, but the D.C. Metrpolitan Police Department’s (MPD) annual budget is roughly half a billion dollars. That is to say, while every government agency guards its budget allocations jealously, the import of such cuts are unlikely to have resulted in the dramatic crime increases seen to date. Indeed, as happened in several other cities, homicides and violent crimes fluctuated in the years since 2020 and those changes do not seem directly correlated to increases or decreases in police budgets. Moreover, the District didn’t pass or implement anything vastly different from other major cities, many of which saw significant drops in homicides in 2023. The attempt to overhaul D.C.’s criminal code was blocked by Congress early in 2023, meaning the biggest changes to criminal laws never took effect.

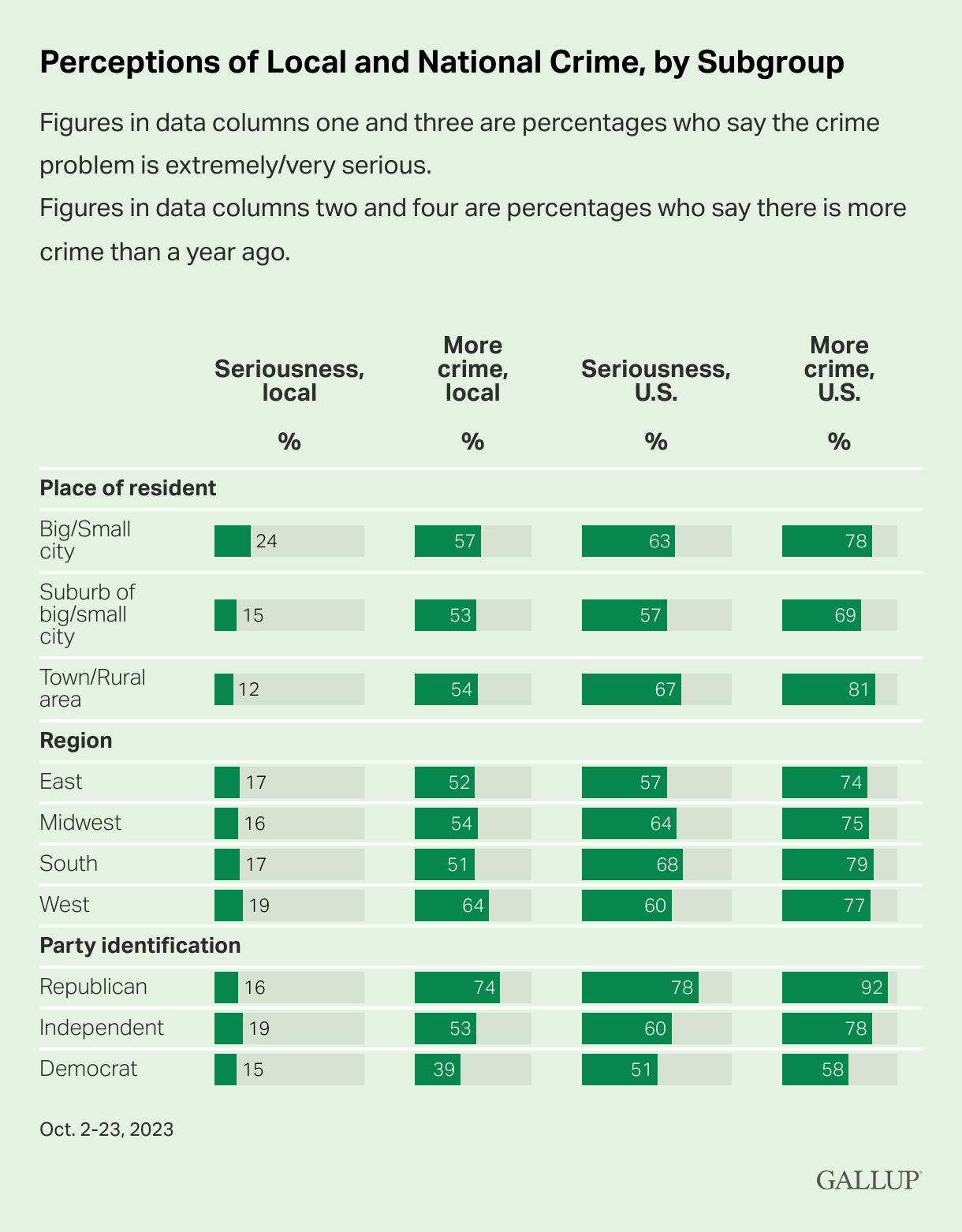

Although the official numbers will not be available until fall, the nation’s homicide rate appears to have had a record one-year decline last year. As Jeff Asher noted in his excellent newsletter on crime data, Jeff-alytics, the politics and the realities of crime don’t match up. According to Gallup, more than 75 percent of Americans think crime is up nationally, despite a pretty clear decrease in violent and property crimes that accompanied the record homicide drop. As the graphic below shows, when a lot of people think crime is up, there is an increased perception it is a “serious” issue, meaning it becomes politically convenient to message on crime, despite exaggerated fears in much of the country.

Notably, just over half of respondents believe crime is up locally, compared with two-thirds nationally. This implies the very local problem of crime may have its largest salience in national politics, where electeds typically have the least influence on crime policy. While this is may be tempting for politicians to run on, doing so is governing by vibes and not data.

Federal intervention in D.C.

Although the federal role in crime control is limited, there are ways to help states and cities tackle their crime problems. In late January, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland announced an initiative to fight violent crime in D.C., increasing prosecutorial resources and data to aid investigations.

While D.C. holds a unique position as a self-governed federal jurisdiction, the initiative is similar to recent DOJ efforts in Memphis (November 2023) and Houston (September 2022), following spikes in homicides and suspected gang crimes in those cities. With the same correlation/causation caveat in mind, it is worth noting that Houston’s homicide rate fell 22.5 percent in calendar year 2023.

Time will tell how effective these federal efforts will be, but it is clear local efforts have failed thus far.

What went wrong in D.C.?

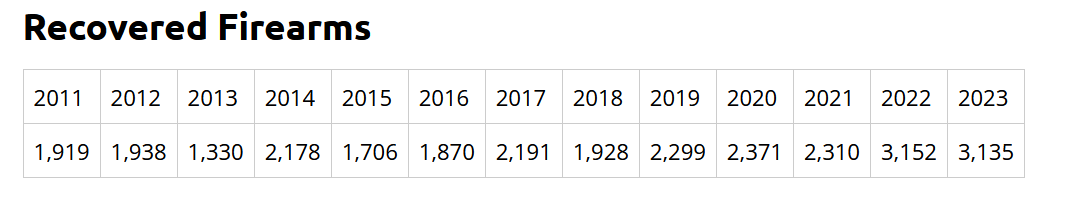

As I’ve noted before, MPD tends to focus on getting guns off the street (gun recovery) as their anti-violence strategy, raising serious constitutional and civil liberties concerns. As the charts below show, though MPD stepped up its gun recovery in 2022, murders in 2023 soared to heights not seen in more than 20 years.

The local newsletter D.C. Crime Facts by the pseudonymous Joe Friday blames several other issues for D.C.’s crime problems. Among these, he includes the catastrophic failures and the loss of accreditation of the D.C. crime lab. Unable to process evidence for court, successful prosecutions relying on forensic evidence were made nearly impossible. (The crime lab regained its accreditation in 2023.)

Friday also cites a lack of will to prosecute gun offenders and charge other violent offenders as felons:

While specific shootings are often sparked by social media insults and personal disputes; the underlying problem is these groups of armed men with longstanding grievances against each other and no fear of consequences for their actions. “Taken together, officers, and surprisingly even many Violence Interrupters, described a feeling of impunity among many people on the streets that may be encouraging criminal behavior.” It’s worth diving into why these offenders have this “feeling of impunity” despite having an average of ten previous adult arrests (with the possibility for even more uncounted juvenile arrests).

For regular readers it will not be surprising that this sense of impunity stems largely from a lack of prosecution. The United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) has one of the lowest prosecution rates of any big city prosecutor in America and it’s no different for this population of highest-risk homicide suspects:

The average of 10 arrests for 12 offenses for each suspect only results in ~6.9 charged cases.

Of those 6.9 cases the USAO ends up dropping 3.6 or 52 percent of them. This can be the result of the USAO deciding the case was too weak, a plea bargain, a loss on the suppression of evidence, “prosecutor discretion” or other factors.

While the average homicide suspect has 3.1 prior convictions, only 54 percent have any prior felony conviction. This suggests that a lot of these convictions are for misdemeanors. In other reports we’ve seen this occur from plea bargains allowing the suspect to plead guilty only to a misdemeanor or the USAO downgrading the initial charges from a felony to a misdemeanor.

For example, out of 1,015 felony assault “convictions” 43 percent of them were for only misdemeanor offenses; primarily due to plea bargains

One example of “downgrading” charges is a case where the suspect caused "fractures to the facial bones" when punching the victim six times (on camera), was charged by police with Aggravated Assault (a felony) but the USAO only charged the suspect with Simple Assault (a misdemeanor).

Despite all of these prior arrests, only 40 percent of homicide suspects ever spent any time in prison before the murder. This is directly because of the USAO’s prosecution “filter” declining, dropping and pleading down charges far more than other big city prosecutors.

Friday makes very persuasive points, as it is very hard to argue that MPD and the judicial system are keeping D.C.’s streets acceptably safe. That said, certain assumptions inferred from these facts need clarification.

First, while I agree that charging someone with a misdemeanor for breaking someone’s face seems like an inappropriate downgrading of charges, the overwhelming number of convictions at all levels of government come from plea bargains, for good and ill. It is fair to argue that the USAO is undercharging or dismissing too many cases in its plea agreements, but a reader unfamiliar with how the system operates may blame plea bargaining itself. (Some commentators have argued forcefully against the practice, but that is a separate argument for another time.) The discretion is built into the system, but D.C.’s system in particular is not keeping dangerous people off the street.

Second, as Friday notes in the post and I’ve discussed before, MPD officers know that a small percentage of offenders are responsible for a majority of the major crimes and homicides. The data Friday puts forth strongly supports that most homicide offenders have the proverbial long rap sheet; a considerable history of arrests and convictions. But again recalling the correlation/causation fallacy: most people with multiple arrests and convictions will never commit murder.

The key–which is, admittedly, much easier said than done–is identifying offenders who genuinely pose a threat to the community. Provide help and a positive path forward to those in at-risk situations and networks, but incarcerate when necessary. No one will be perfect at it, but a culture of impunity reported by the people working closely with at-risk individuals cannot possibly foster public safety.

Looking ahead

Because so many factors can influence crime, anyone predicting what will happen year to year is either guessing or has an agenda.

Personally, I’m cautiously optimistic about my own neighborhood, having seen a marked increase in police patrols and MPD leadership reaching out to community members to ask what we want. But I don’t know how other policing districts are faring, so I’m going to go find out. To that end, in addition to commentary on national policing issues as I have in the past, I will write D.C.-specific updates to see if the capital region is headed in the right direction. Next up: the D.C. Council is set to vote on an omnibus crime bill Tuesday February 6.

Hopefully, this time next year will see a significant decrease in crime and violence across the city as well as the rest of the country.