Skilled immigration is one of the most straightforward ways to address the ongoing American labor shortage. High-skill immigrants provide economic and social benefits to the country and are integral to furthering entrepreneurship and innovation. The education and training skilled workers receive abroad can import knowledge from other nations into the United States, filling crucial knowledge gaps in both the private sector and the academy, thus keeping America at the cutting-edge of technology.

Work visas versus green cards

For foreign-born persons to work in the United States, they must obtain a work visa, a green card, or U.S. citizenship. A green card allows a person to work and live in the United States with all of the rights, freedoms, and tax burdens of an American, save voting privileges. Green card holders still face certain constraints—including restrictions on long-term travel and deportation for criminal offenses—but generally a green card provides the most freedom for a non-citizen to work and live in the United States.

Work visas, however, severely limit work permissions and travel freedom. To obtain a work visa, an applicant is typically sponsored by a particular company, which ties that person to not just one industry, but to the specific company that sponsored them. Even in the best cases, this can hamper an individual's ability to find work elsewhere within their own work field, let alone another profession. In the worst cases, employers can exploit workers who depend on the sponsorship and employment of their firm to stay in the country. On top of these considerable work limitations, work visas also come with harsh foreign travel restriction that can prevent workers from visiting the families in their home countries for years at a time.

While approximately 140,000 work visas are available every year, the harsh labor and travel restrictions diminish workers' quality of life. These problems are compounded by the relatively short duration of most work visas, which require applicants to re-apply every few years, leaving many workers unsure of their medium and long-term futures. They can live under constant fear that their renewals will not be accepted and they will be forced to choose between abandoning their lives here or staying and working illegally to hold on to their lives.

Family matters in the green card process

For about a decade, roughly one million green cards were issued every year. In 2020, this number decreased nearly 30 percent to 707,362. Of the green cards awarded in 2020, 27 percent were awarded to the husband or wife of a U.S. citizen and almost half—45 percent—were awarded to unite U.S. citizens with spouses, children, and parents.

Although the overall numbers are lower, the percentages are roughly consistent with the previous decade. The proportion of green cards awarded to spouses ranged from 23 percent to 29 percent, and the proportion of green cards awarded to immediate family members ranged from 41 percent to 49 percent. If one includes extended family members, the percentages of green cards going to relatives of U.S. citizens ranges between 53 percent and 60 percent over this time. Likewise, an additional seven to ten percent of green cards go to the spouses and children of alien residents.

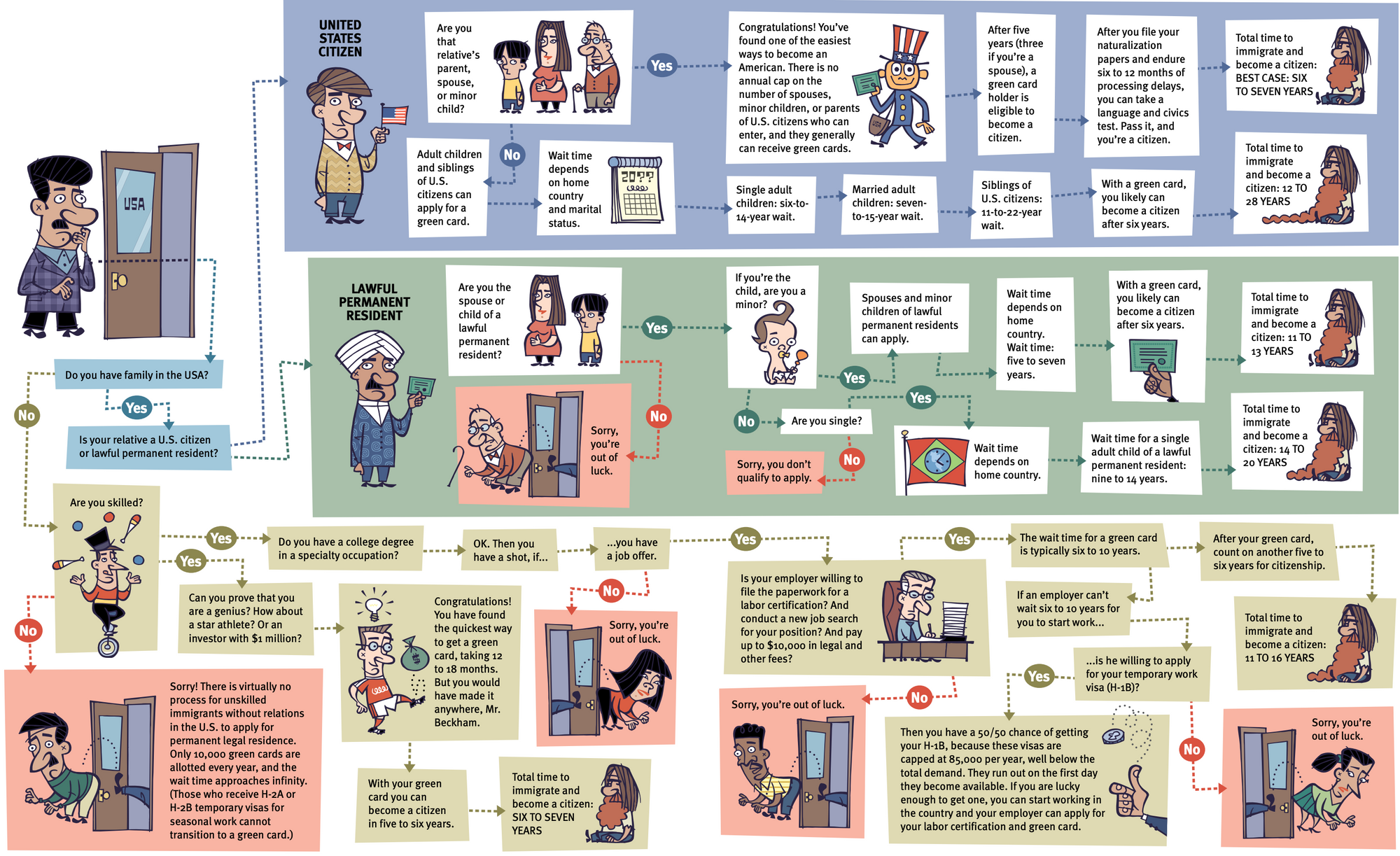

Thus, the majority of green cards over the past decade (between 62 and 69 percent each year) have been awarded to family members of people already in the United States, with large majority of those going to family of U.S. citizens. (The Department of Homeland Security makes green card and immigration data available here.) In any case, the process to attain a U.S. green card is long and arduous.

Expanding employment-based preferences

The proportion of employment-based preference green cards issued over the past decade ranged from 12 to 16 percent of all green cards issued. These new green card holders comprise a variety of walks of life, including professionals with advanced degrees, aliens of exceptional ability, skilled or unskilled workers, and several other categories. High-skill immigrants without extant family bonds in the United States thus receive very few green cards in any given year.

When immigrants apply for employment-based green cards, they undergo an extensive vetting process, including to ensure that they are not taking opportunities away from low-income Americans. Although this may be laudable in the abstract, high-skill immigrants are not competing directly with low-income and typically unskilled American laborers.

Approving more green cards for high-skilled immigrants solves problems both for valuable workers and the U.S. labor market. Short of that, policymakers should change the structure of work visas so that foreign workers can have more freedom to see their families and improve flexibility to change jobs or industries.