A college degree can be a path to upward mobility, but the cost is steep. Students not only need to pay for tuition and textbooks, there’s also an opportunity cost to enrolling in school. College students, for the most part, do not work full-time. To attend college, they must sacrifice not only a full-time salary, but also miss out on labor market experience that could increase their earnings down the road.

FREOPP’s analysis of college return on investment (ROI) assumes a “traditional” college student who enrolls in school full-time at the age of 18 and does not work while enrolled. But it’s possible to change these assumptions to reflect the fact that not all college students pursue this traditional route. In particular, some prospective students may be wondering whether it’s a good idea to take on less than a full-time course load and find a job to help cover college expenses.

About 2 million of the nation’s 10 million traditional-age college students are enrolled part-time. The obvious advantage to part-time enrollment is that it leaves more time for work, so that the opportunity cost of attending college isn’t quite so great. Lost wages while enrolled are often a more significant cost than tuition and fees, so recouping these can be beneficial. The downside to part-time enrollment is that it takes longer to earn the college degree—which delays any earnings benefits that come with that degree.

Whether it’s a good idea from a financial perspective to attend college part-time or full-time is therefore an empirical question. Does the lower opportunity cost of part-time enrollment compensate for the delay in earning the degree? We can use FREOPP’s ROI data to answer this question.

Consider the bachelor’s degree in political science at the University of Pittsburgh. I estimate that, for students who enroll full-time and graduate in four years, this degree increases lifetime earnings by $303,000, after subtracting costs.

But if a student enrolls half-time and finds a half-time job, the same degree has an ROI of just $186,000. The student benefits from his half-time wages while enrolled, but it takes him eight years to complete the college degree. It takes four years longer for the student to realize any earnings benefits from his political science degree, shortening his career in college-level work by that much time. The wages he earns while enrolled are not enough to compensate for the delay.

What if the student enrolls in college half-time and finds a full-time job while taking courses? While he might sacrifice some sleep, he could earn more wages while enrolled. But the delayed entry into the labor force is still costly. The ROI of the University of Pittsburgh’s political science degree under these assumptions is $300,000—virtually the same return as enrolling full-time with no work.

These patterns hold for bachelor’s degrees more broadly. Median ROI for a four-year college graduate who enrolls full-time and finishes within four years is $343,000. ROI for graduates who enroll half-time and work half-time is $229,000, while ROI for graduates who enroll half-time and work full-time is $339,000. Enrolling in college full-time, even with no work, is usually the best financial decision.

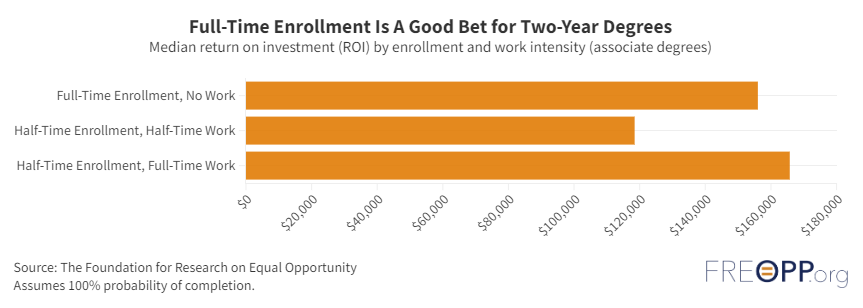

Similar patterns apply for two-year degrees. The median associate degree has an ROI of $156,000 assuming full-time enrollment and on-time completion. This drops to $118,000 for two-year college graduates who enroll half-time and work half-time, but rises to $166,000 for graduates who enroll half-time and work full-time.

Because the labor market benefits of an associate degree are much smaller, delaying graduation isn’t quite as costly. Even so, half-time enrollment and full-time work only modestly increases this degree’s ROI, relative to the baseline of full-time enrollment and no work. That small increase may not be worth the long hours and late nights.

There are other costs to part-time enrollment not accounted for here. Due to a lack of reliable data on part-time students’ graduation rates, all the calculations above ignore the risk that the student will drop out. But enrolling part-time stretches out the college experience and increases the risk that life will intervene and force the student to abandon his studies.

College students may also be more limited in the sorts of jobs they can pursue while enrolled. These jobs will need to have flexible schedules to accommodate coursework and, for students enrolled in person, be reasonably close to campus. As a result, current college students often cannot pursue the highest-paid work available to them and must settle for a more flexible job with lower pay. As a result, even students who work full-time while enrolled are unlikely to fully recoup the opportunity cost of lost labor market experience.

Other evidence suggests that full-time enrollment is usually the best financial decision for students, if it’s viable. A college-completion initiative in Ohio offered students comprehensive financial and academic support if they consented to enroll full-time; the program boosted both degree completion and earnings after graduation. In addition to helping students earn their degrees faster, full-time enrollment likely leads students to commit to their education more wholeheartedly.

Whether to attend college full-time or part-time—or indeed, whether to attend at all—is a personal one that depends on many factors unique to the individual. But for prospective students looking to maximize the financial benefits of college, full-time enrollment is usually the more promising route.